The Man Who Led Peary to the Pole (or very close)

Robert Peary gets all the accolades (and plenty of warranted skepticism) for being the first to the North Pole, but he would never have made it there (if he did) without the intrepid master mariner and ice navigator Bob Bartlett. History has focused primarily on the controversy surrounding whether Peary indeed made it to the North Pole, and on Matthew Henson’s presence during the final push.

Overlooked is Peary’s fateful decision NOT to take Captain Bob Bartlett.

Here’s what happened, but first a bit of background and context. Robert Abram Bartlett was born in August 1875 in Brigus, Newfoundland. He came from a long line of ancestors—the famous “Bartletts of Brigus”—who had skippered ships in the seal and cod fisheries for generations. His uncles John and Sam, and his father William, had been involved in the search for traces of the lost Franklin Expedition in 1845. His great-uncle Isaac captained the Tigress in 1874 searching for Charles Francis Hall’s lost Polaris, eventually rescuing survivors of that shipwreck on a raft of ice in lower Baffin Bay.

So, seagoing adventure coursed through young Bob Bartlett’s veins. Throughout his childhood and teens, he joined his father on sailing voyages, and at seventeen he commanded his first schooner, the Osprey, returning from Labrador’s dangerous waters with a full cargo of cod. He spent the next six years almost always at sea, making runs to the Caribbean and Latin America and across the North Atlantic. By 1898, at the age of just twenty-three, he was awarded the title captain and master mariner.

Bartlett’s first experience with Peary came when he served as first-mate under his uncle John Bartlett aboard the Windward during Peary’s first North Pole Expedition 1898-1902. On that journey, Peary returned from a three-month sledging trip with severely frostbitten feet. Bartlett helped lay Peary out for surgery, assisting the ship’s doctor as he administered ether, then holding Peary down as the doctor amputated eight of his toes.

Peary was clearly impressed by the young man, enough to enlist him as captain and ice master for his next two North Pole attempts, in 1905-6 and 1908-9, aboard the spectacular 1,000-horsepower steel-hulled SS Roosevelt.

On the second expedition, Bartlett had earned so much trust that after wintering at the northernmost tip of Ellesmere Island, Peary chose Bob Bartlett to lead the “Pioneer Party” across the Polar Sea ice toward the North Pole. For nineteen days, Bartlett and his advance sled team set the course, broke the trail, built igloos and prepared food for Peary and the main party following behind. The terrain was rough and undulating, the sharp sea ice slicing through their mukluks and shredding the wooden sled runners. The bitter cold and howling winds had rendered Bartlett’s face and hands frostbitten, but he drove onward for his leader. Bartlett was hopeful that his grit and navigation skill had earned him a chance at the final push for the pole.

But on the first of April 1909, Peary took Bartlett aside. They stood just shy of 88-degrees latitude—only a few days, a week at most, from the North Pole. Peary thanked Bartlett for his tireless trail breaking, his route navigating, his dedication. But he said he wanted Bartlett to return to the Roosevelt; he was taking Matthew Henson instead. Henson was the better dog driver, Peary said. Bartlett couldn’t argue that fact; it was true.

But Bartlett was the far superior navigator, an expert with a sextant, able to take observations and confirm their position and provide definitive proof that they’d reached the pole. Peary’s decision was final, however, and all Bartlett could do was lower his head and thank Peary for taking him this far. Peary, sensing Bartlett’s deep disappointment, turned to Bartlett. “It’s all in the game,” Peary said, his eyes fixed toward the north. “And you’ve been at it long enough to know how hard a game it is.”*

Bartlett was crushed. He was within 135 miles of the farthest end of the earth. “Perhaps I cried a little,” he would later say of being forced to turn back. “It was so near.”** Before Bartlett left, he walked some five miles north of the igloos into hammering winds, taking a final observation at latitude 87-degrees N. 48’.

On his return to civilization, Peary reported to the world that on April 6, 1909, he, Matthew Henson, and four Inuit men had stood at the geographic North Pole. There’s a photograph of the men holding flags. But his homecoming, and claim, were marred by controversy. He soon learned that American explorer Dr. Frederick Cook claimed to have reached the pole in April of 1908, a year before Peary. And Peary’s own records were analyzed, pored over and doubted in the first years following his return. In 1911, for three days Peary withstood grueling hearings by Subcommittee NO. 8 of the Committee on Naval Affairs, during which they grilled him about his scant observations and dubious missing diary entries.

Although Peary was eventually granted the title of discoverer of the North Pole by nearly every geographical society on earth, his claims remain very much contested, sullied by the asterisk that says “*disputed.” In the 1980s, the National Geographic Society scrutinized documents which had recently surfaced and determined that Peary had most likely falsified his records.

He could have saved himself a lot of headaches by taking Captain Bob Bartlett along on that final, fateful push to the pole.

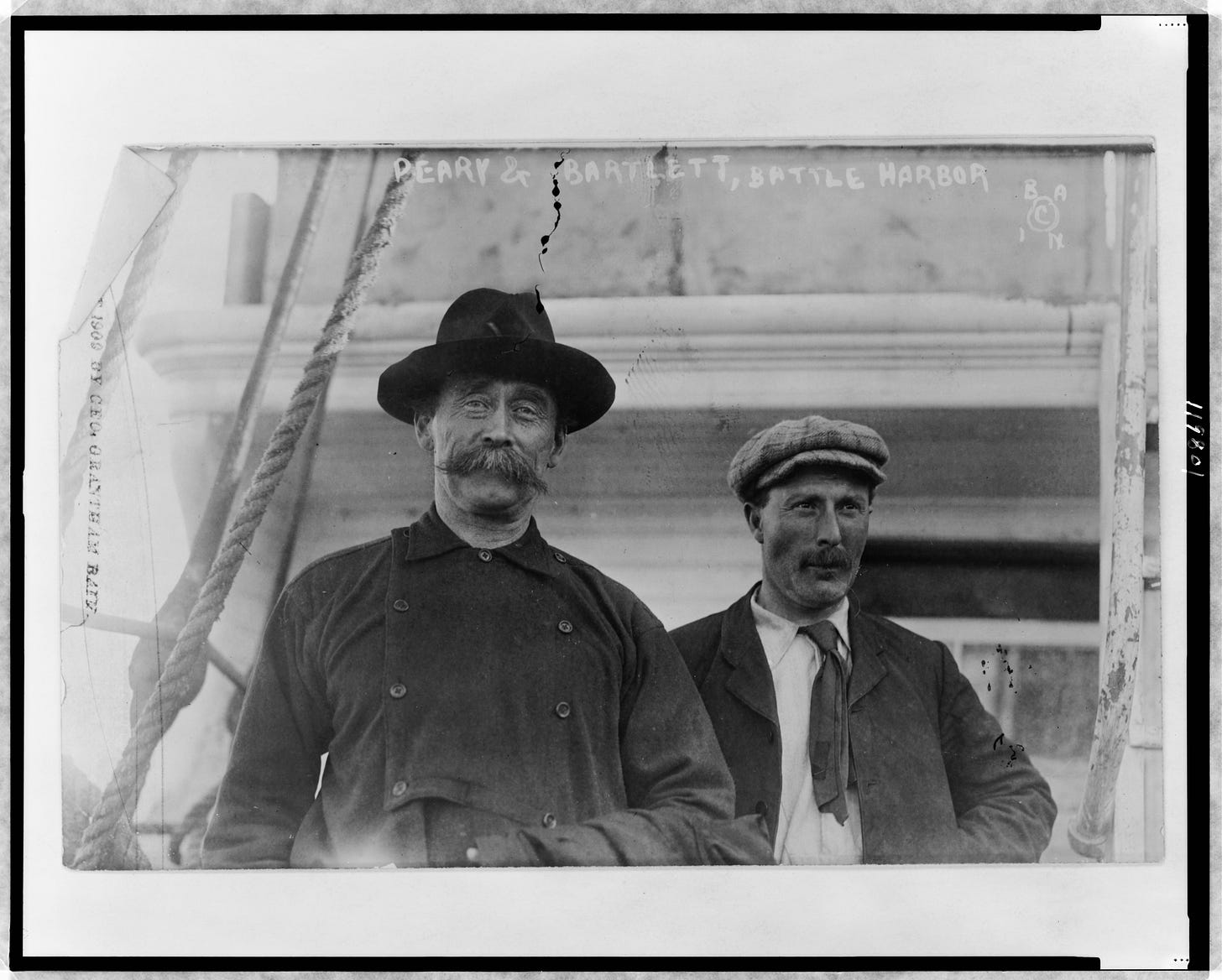

(Captain Bob Bob Bartlett (right), and Robert Peary. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Captain+Bob+Bartlett&title=Special:MediaSearch&go=Go&type=image)

* From The Log of Bob Bartlett, p. 195.

** From Harold Horwood, Bartlett: The Great Canadian Explorer, 87.