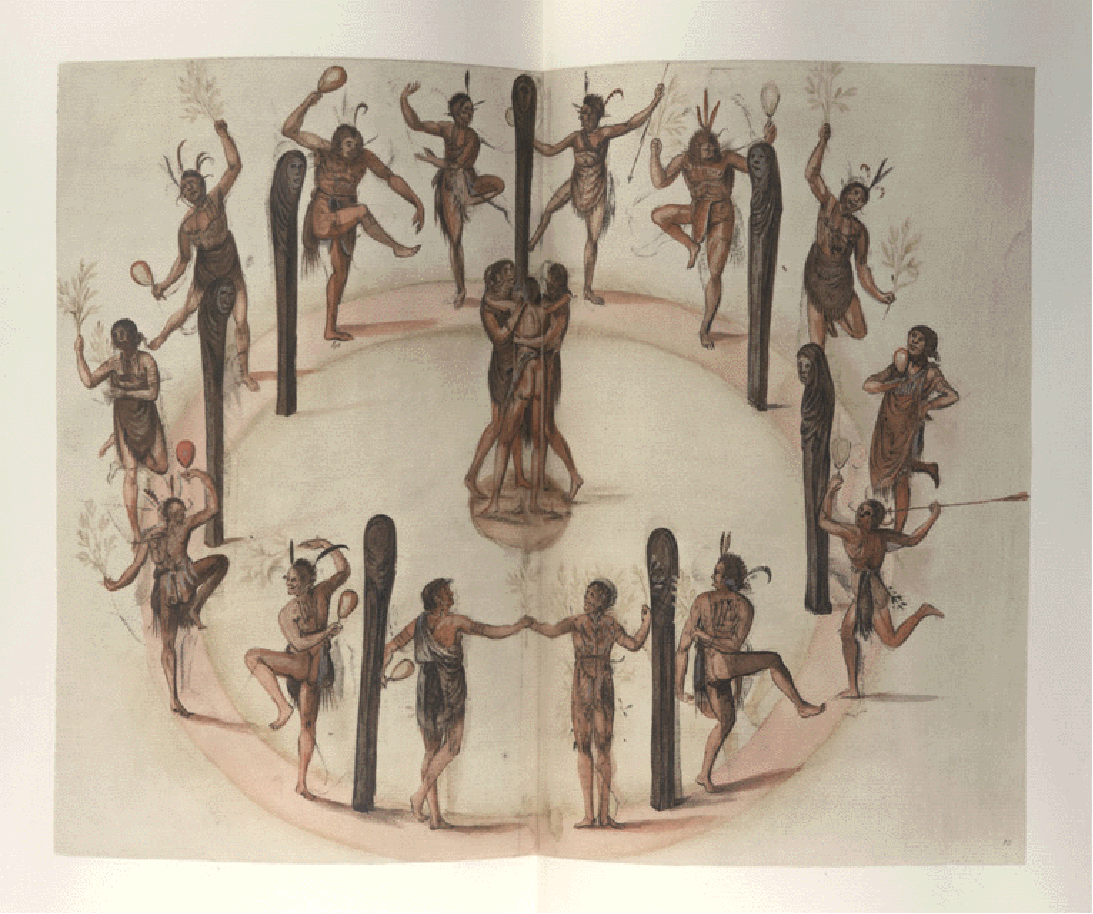

Secotan Ritual Torture Dance

Chapter One

The child was born that night. After the attack Manteo organized the burial of the six dead colonists in an enclosed cemetery between the fort and the bay shore, interring the corpses in the English way to appease White but returning in the night, using his own measures to ensure that they were dead and properly buried. When he came back to the Dare’s house at dawn the servant Agnes Wood—having midwifed through the night—stood beside Eleanor. Eleanor’s eyes were closed, her face drawn and pallid, and she barely breathed. Manteo reached to touch her sweltering skin, afraid that she would perish.

“She bleeds,” Agnes told Manteo.

“The baby?” asked Manteo. He could see the infant’s form cradled in Eleanor’s arms beneath the coverings.

“No, she seems well enough,” replied Agnes. “But Eleanor, she bleeds even now. I know not what to do.”

There was no time to paddle to Croatoan Island for the tribal priest-doctor versed in wisakon herbal medicines to help staunch Eleanor’s bleeding. He would need to do this himself. Manteo hurried to the woods, returning to the Dare’s small hut with a handful of white plantain and snakeroot, a bough of pine and some tufts of silkgrass. Ananias Dare and John White remained outside, pacing at the half-timbered house’s entrance, White drawing in the dirt with his boot toe. Knowing what he was about to encounter, Manteo suppressed his own urges and desires.

“Ease her burden,” said Ananias as Manteo stooped to enter the building.

The smell of blood permeated the warm room, sweet and ferrous in Manteo’s nostrils as he inhaled deep. The essence swirled onto his palate, settling like a yearning on his tongue, like the ancient craving for bear meat. He closed his eyes and concentrated, willing aside his appetite. He knew he must be strong, must stay focused on her needs and not his own.

He sat in the dark corner of the low-ceilinged, fire-lit hut. Eleanor moaned, throaty and guttural as a wounded animal. The newborn nursed through her mother’s cumbrous, uneven breathing. Manteo placed the herbs in a wooden mortar and with a blunt pestle he pulverized the leaves and roots as he had seen his father do, mashing and then stirring them in short circular strokes. He squeezed pine pitch and resin into the mortar, chewed on stalks of silk grass and into the paste he spat, working the curd into a thick grume to use as a clotting poultice against her blood rush.

Manteo rose with the mortar and approached the birth bed, asking Agnes to tend the fire and light the oil lamp on the mantel. The girl did as Manteo bid her, adding dried cedar to the fire. Manteo leaned close, lifting the stained sheets up and over Eleanor’s ankles, then her calves, rolling the beddings finally above her knees, which he splayed gently outward to expose her. Her white thighs were bespattered with blood and mucous afterbirth, and beneath her rested a bowl of pooling blood.

“More light,” he whispered to Agnes, who held the lamp a safe distance away. To Eleanor, Manteo was firm. “Hold still for this.”

Manteo steeled himself for what came next, for what he knew he must do. He cupped a handful of the thick herbal pomace and reached down between Eleanor’s legs, sliding his salved fingers into and up her birthing canal, spreading the paste deep within, along her channel walls even as she shuddered against his intrusion. He withdrew his hand, daubed another palm-full of the poultice, and caulked the unguent to the entrance of her womanhood. Then he waited, uneasily regarding the blood bowl. After a time her bloody effusion slowed to droplets, then ceased. When he felt certain the bleeding had stopped he draped a new bedsheet over her and spoke to both Eleanor and Agnes.

“She must stay very still the rest of the day, and then again tonight,” he said. He pointed to the herbal mixture, instructing Agnes, “Daub her again every few hours, both inside and out. I will bring more wisakon herbs later, and dispose of her blood for you … to keep from attracting predators.”

Manteo wiped the bloody mucous from his hands onto a gauzy towel near the bedside, then threw the soiled rag in the fire; it sparked luminescent scarlet. He turned from Agnes so that she would not see how his hands shook. Eleanor opened her eyes now. Her breathing calmed, she smiled slightly.

“Manteo,” she said faintly. “Am I to die?”

Manteo shook his head, held his palm out to quiet her.

“Not tonight. Now sleep.”

The infant had finished feeding and lay curled against Eleanor’s breast. In the firelight Manteo observed the dark reddish color of the newborn’s skin, the child’s visage cast over with a crimson caul.

“She’s beautiful, isn’t she?” asked Eleanor, stroking the infant’s hands. Then, noting Manteo’s long gaze, she added, “Her deep color. Must be a birthmark. And her fingernails, how fully formed already.”

Manteo put his hand on Eleanor’s knee. “You both need to rest. And you should eat later, for strength.”

Manteo, walked outside and faced anxious Ananias Dare and John White.

“What of her condition?” asked White.

“She will strengthen,” Manteo said. “The baby is sound.”

The two colonists embraced one another, then nodded to Manteo, one each in turn shaking his hand.

“Our debt to you is deep,” said John White, now both father and grandfather.

Ananias Dare started to speak, but words would not come. He turned and walked inside to be with his family.

(To be continued …)